Category: Q&A — Published:

Here the artist discusses with Sofia Victorino (Daskalopoulos Head of Education & Public Programmes) how he began making films, the role of the projectionist, and how the concept of ‘wasting time’ informs his work.

Sofia Victorino: What prompted you to make your first Nyau films?

Samson Kambalu: I have always made playful ‘Nyau’ films, even as home videos – watching improvised itinerant films as a child growing up in Malawi has had that effect on me. But I was only able to fully realise my current Nyau Cinema aesthetic with the discovery of film editing software on my personal computer. Film making then became more spontaneous, and the Nyau Cinema praxis blossomed from that.

“I am not wholly converted to the idea of time as a scarce resource […] This attitude informs most things I do, including the kind of art I am interested in.”

Samson Kambalu

SV: Time and play are hugely important concepts in your work. Why?

SK: Time and play is what moves the way of looking at the world I grew up with in Africa; I only left Malawi when I was 25. Malawi is a gift economy and its conception of time is non-linear – time is conceived as an abundance to be ‘wasted’ in creative play, which manifest in a performative culture, Nyau, and in prodigious gift giving within everyday life. I am not wholly converted to the idea of time as a scarce resource – a commodity. This attitude informs most things I do, including the kind of art I am interested in.

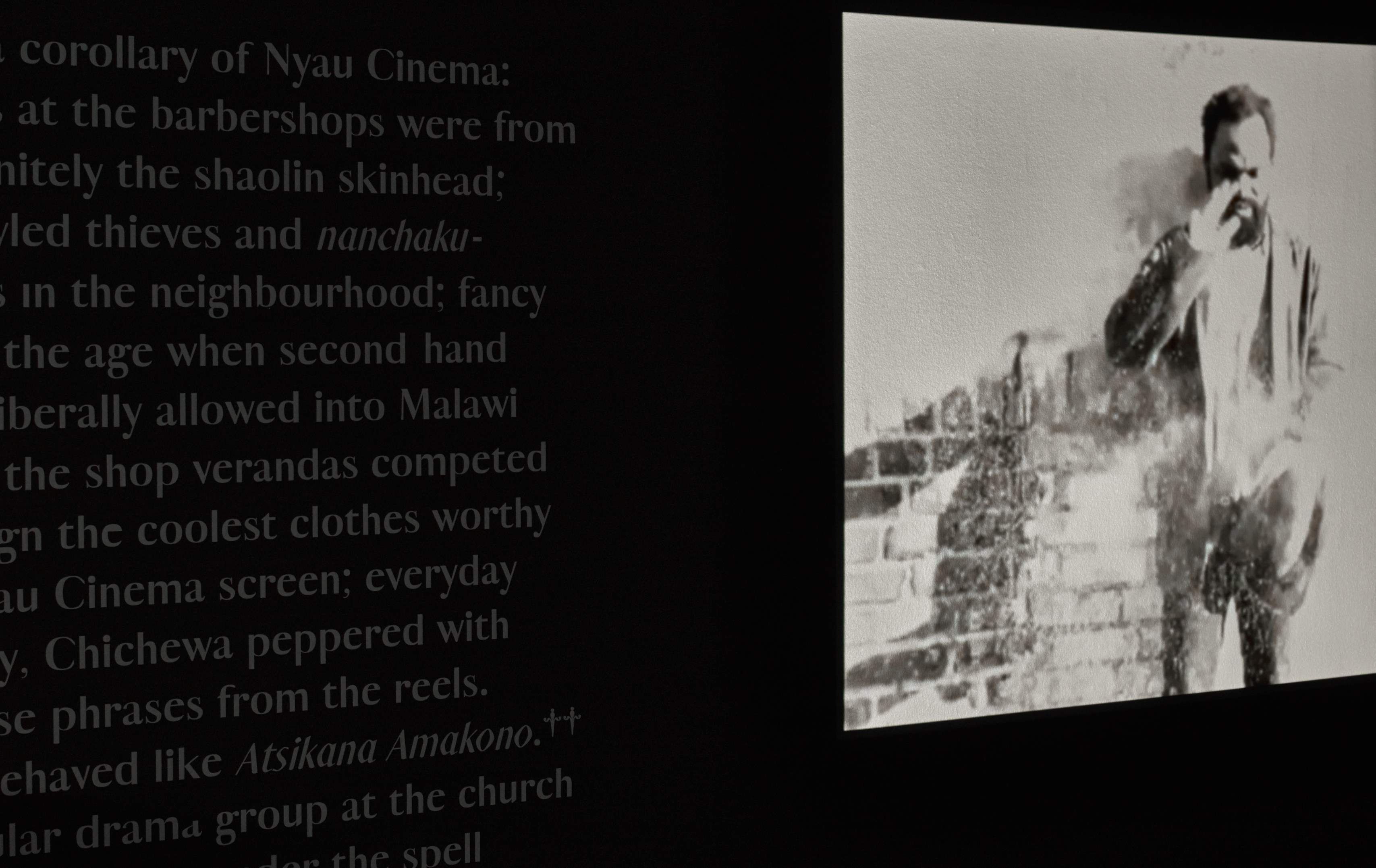

Installation view, Samson Kambalu: Introduction to Nyau Cinema, Whitechapel Gallery 2016. Photo Stephen White

SV: The form the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition Introduction to Nyau Cinema takes is evocative of a magazine spread. And the text presented on the walls is not meant to be read sequentially – there is no right place to begin or end. Why was this important?

SK: One stumbles into Nyau Cinema – then you come and go as you please. Each film flickers and lasts less than a minute. You can look at the installation and experience it from any angle and get the picture – time as gift.

“When I was growing up in Malawi a good projectionist served the same role as a Nyau mask in pre-colonial times, to bring back magic among the people…”

Samson Kambalu

SV: In Casablanca V (2016) we see a child looking into what we suppose to be a screen. The text on the walls narrates a childhood experience – that of watching films in church halls in Malawi. I am fascinated by your description of the role of the projectionist – almost like a magician. Can you talk about these two things?

SK: For children time is always a gift, the world is already a magical place for them and they will play and embrace the present moment anyhow. In the adult world magic is lost to necessity, and cinema is one portent way of re-enchanting the world.

SK: When I was growing up in Malawi a good projectionist served the same role as a Nyau mask in pre-colonial times, to bring back magic among the people, which is really another manifestation of time as gift. Hollywood and foreign films would be ramped or re-edited for a more instantaneous experience of film. Cinema was more an active event than passive theatre.

SV: You also write and make music. Can you tell us how these things come together in your working process and practice?

SK: Good writing, like good music or art, is a gift.

Samson Kambalu: Introduction to Nyau Cinema (23 August 2016 – 8 January 2017) is on show at the Whitechapel Gallery in Galleries 5 & 6.