Published:

In celebration of our current exhibitions, we’re sharing vivid works of art across the streets of East London. Keep your eyes out over the next few weeks for images of Eileen Agar‘s spirited canvases, which add some much-needed colour to this gloomy, grey summer. Be sure to book your tickets to see these works and more in Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy, on view until 29 August.

If you encounter one of our posters outdoors, please snap a photo and tag us using #surrealsummer2021 on social media.

The early 1930s were a time when Eileen Agar was becoming aware of her identity as a woman artist and developing an understanding of her gender’s impact on her career. Through her work on the journal The Island, she developed a theory that she called ‘womb-magic’:

“In Europe, the importance of the unconscious in all forms of Literature and Art establishes the dominance of a feminine order over the classical and more masculine order. Apart from rampant and hysterical militarism, there is no male element left in Europe, for the intellectual and rational conception of life has given way to a more miraculous creative interpretation, and artistic and imaginative life is under the sway of womb-magic.”

This thinking informed most of her work during the early 1930s, including Madonna with a Cat’s Cradle (1934), which possesses an atmosphere of burgeoning optimism and tender equanimity.

As the Second World War ended, Agar “felt like something new and marvellous ought to happen, but I was exhausted and humdrum, more tired and dispirited than usual”. She describes this period as a physical and spiritual famine. Yearning for a change of scene, but with travel outside of the country difficult, she and her husband Joseph Bard visited Cornwall and Ireland to replenish their imaginations. Slowly Agar returned to painting as if she were “renewing a belief in life itself”.

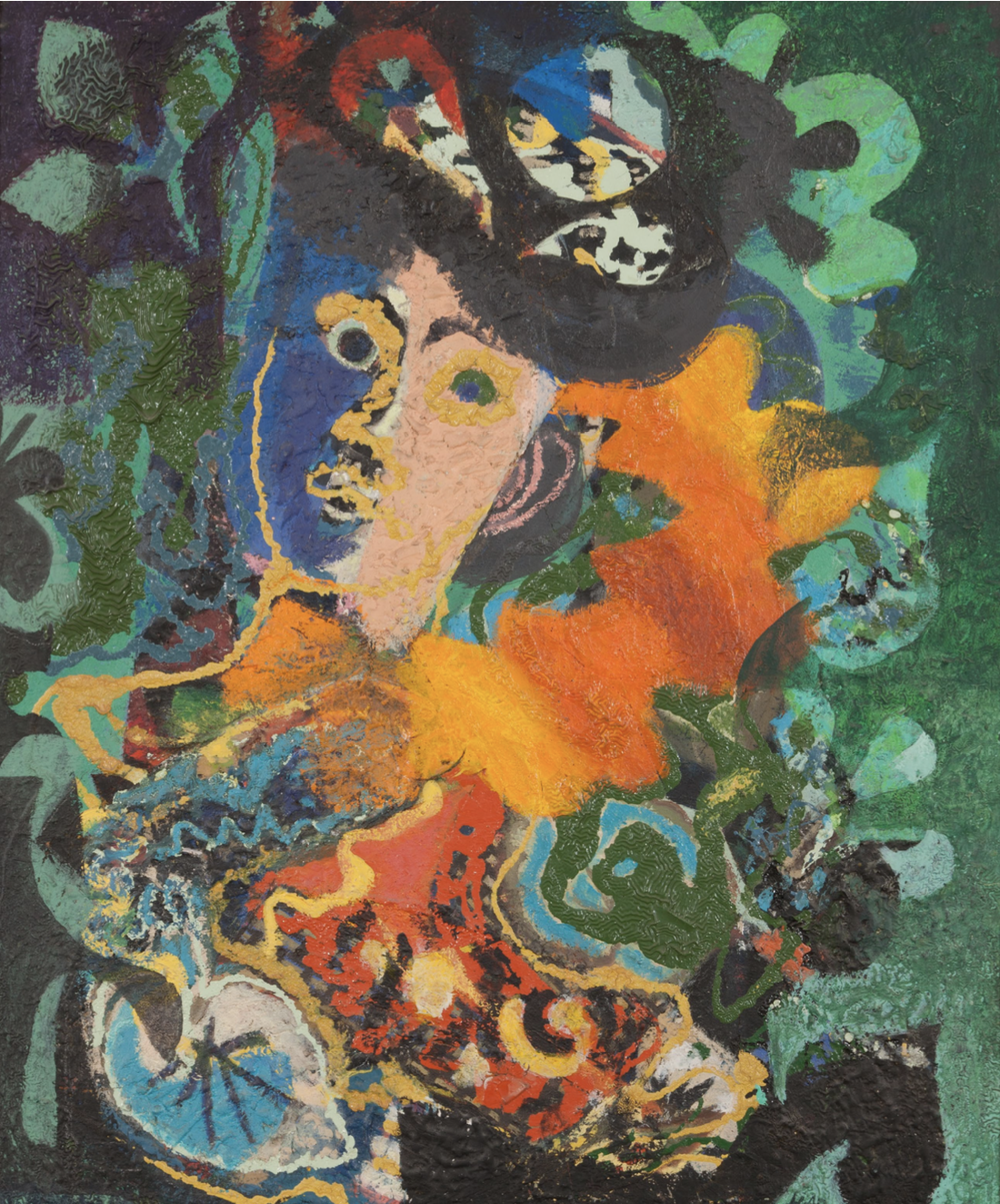

Possibly the first painting she made after the end of the war, Dance of Peace (1945) embodies this budding and tentative optimism. Painted in pastel washes and idyllic forms, the arrangement of dancing figures seems to draw directly from Agar’s processes of collage; layering and overlapping, semi-translucent animals, leaves and faces emerge between the main figures. In direct contrast to the violence of war and the rapid social changes it had wrought, Dance of Peace recalls a pastoral idyll, looking back to humankind’s rural past.

By the 1950s, Agar was enjoying a successful period of painting, travelling and exhibiting, and had begun to feel like herself again after the war. She wrote: “surely room must be made for joy in this world? There has to be hope and celebration”.

Her work was beginning to blur the divisions between collage, drawing and painting and she continued to experiment with surrealist techniques such as automatism, frottage and decalcomania. Agar enjoyed this process and the use of a new paint: “I like working with enamel paint because it is so free”, she wrote. She made a number of works in this vein including Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1960), which feels quite loaded with its curving drips and trails of poured paint. The canvas is dense and disordered, perhaps depicting her conflicted feelings towards her mother and family.