Category: Writer in Residence — Published:

Phoebe Boswell is an interdisciplinary artist working in London. She is Whitechapel Gallery’s Writer in Residence as of January 2022 and will publish a new series of texts available on our website, alongside a series of events with Phoebe over the course of the year.

Ruth Lie (Curator: Public Programmes) interviews Boswell about her work and inspiration.

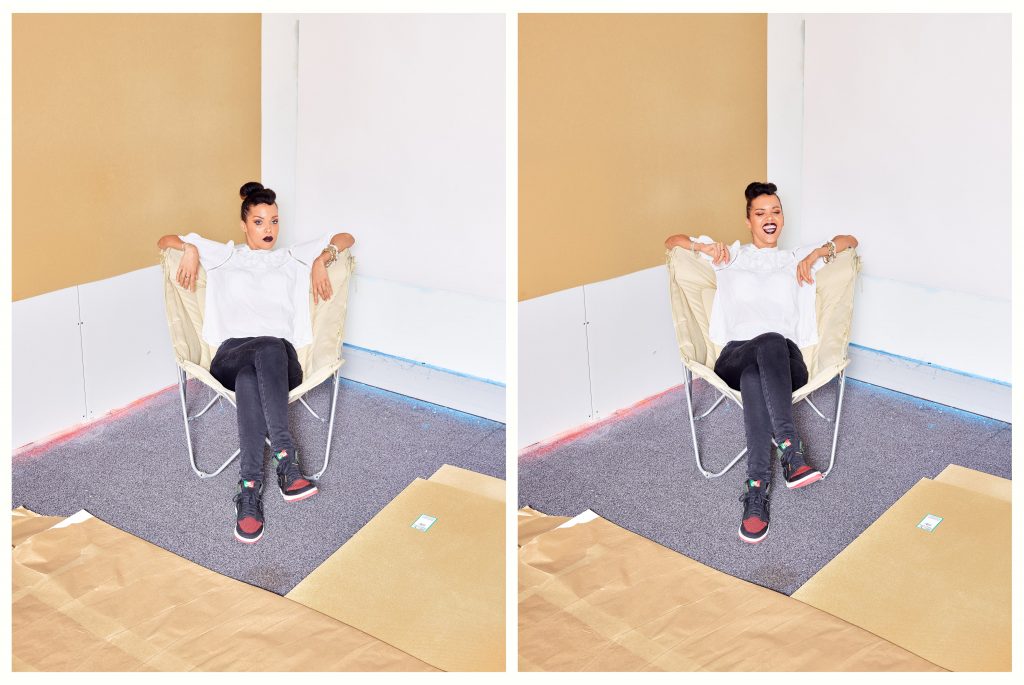

Portrait of Phoebe Boswell. Photo: Emile Holba

Portrait of Phoebe Boswell. Photo: Emile Holba

You are well known for your explorations in drawing, yet your work spans many different mediums- sound, performance, painting, animation, video, and most specifically in this case, writing. How do you think about your writing practice, which is often less spoken about, in relationship to the other ways in which you work?

Writing is an intrinsic part of my thought process. I tend to write my way through the muddy waters of ideas forming. Words navigate. The right words build frameworks, backbones, tent pegs, placeholders, beacons, perimeters – even though oftentimes these words remain private. I love words and respect the importance of language in world-building. Words – and the way we use them – matter. I don’t speak Swahili or Gikuyu, my mother’s tongues, and have always felt the ache of this gap, but equally I feel like this has meant that I create language in other forms, visually and experientially, always attempting to make some sort of communicable language robust yet fluid enough to eek itself into both English edges and Kikuyu corners. Writing helps me to hold the nuance and complexity of us. I hate to be misrepresented or flattened by those who choose not to fully see us and writing is sometimes the clearest way to define the space I wish to occupy – to liberate – for myself and for us. So I write essays to home my practice; I journal to home my heart; I tell stories; I play with poetry sometimes. It has to be said that I’ve never considered myself a writer (I feel like as soon as you say you’re a writer you have to get into the sticky business of whether or not you’re a good writer and who wants to do that?) but being given this writer-in-residence has posed a wonderful proposition as it challenges me to centre this super-important part of my practice. I appreciate the acknowledgement of my writing as I interrogate its form and function. I’m certainly intrigued to see how this plays out.

You have a fascination with observing people, which feeds directly into your work. What else do you draw inspiration from? How much do your own personal, lived experiences influence your work?

I tend to move between the personal and the communal; I try to keep the two in tender balance. If I spend time exploring a communal idea, something that draws together multiple voices, I will then turn back towards myself to recalibrate…and also to acknowledge and salute how generous and generative it is to lay oneself bare. I’m always stunned in gratitude by how people come towards my work when I reach out with questions or provocations to be answered. This comingtogether is miraculous to me; it offers space to sense ourselves and each other. Being vulnerable in my own work reminds me that I’m both unique and universe – my grief is your grief, my joy is your joy, my life is your life. And vice-versa. That’s ultimately what influences my work: a desire to make space for us – while bearing witness to the systemic injustices that plague us all – simply to care for one another. Buoyed by Black feminist scholarship, I ask: what is freedom? What is belonging? What does your voice sound like? What are your safety valves? Can I remind you to breathe? Can we breathe together? Do I feel safe here? Can I provide safety? Who am I? Who are you? Who are we? And how?

How does a fluid process help to alter your outcomes? Can you give an example of a past project that resulted in a surprising shift based on the presence of an audience, or as a result of the duration of the project itself?

My work is fluid, you’re right. I usually begin with a small yet enigmatic premise, something that either titillates of unnerves me, and I’ve learned to trust that this will grow instinctually through process and form itself as it needs, utilising this toolbox of stuff I’ve accumulated over the years: drawing, animation, sound, film, interactivity, and so on. So surprises happen in the studio, even more so when the work involves a chorus of people contributing their voices to it, and then it goes through another shift when it meets its audience. I’ve never not been expanded by how people meet my work, either in the process of the making or in the interaction while it’s on view. I’m an undisciplined reader; I rarely read commitedly from cover to cover, finding myself dancing between multiple books at once, merging multiple meanings. I treat history books with respectful caution; they were written at a specific time by specific people to tell you a specific version of a moment, and this version tends to be what we then widely consider to be fact. I’m much more tuned to a passing of knowledge through oral tradition, I love to learn via the rhizome of testimony: you ask a group of people what freedom is, in this moment, right now, where they are, and they each tell you their heart, and it creates a rhizome of meaning to a thing that is impossible to make fact, to hold, and yet, and yet the chorus is still tangible, and the meaning is in the spaces between. I prefer that. To offer that. Its fluidity seems much more truthful and expansive to me. This is why my work is so multilayered, multiform. I want it to hold multiple inroads and timeloops. I want it to be imbued with the porousness of human fallibility, vulnerability. I’m as fascinated by the past as I am about the future as I am about the right-now. I don’t think this answered your question.

Could you tell me a bit more about the project you’re hoping to develop over the course of the Whitechapel Gallery writer-in-residency programme and how you came to think about water, swimming, and the relationship of this to the black experience?

In this work, I’m looking at the historic implications of water in relation to Black people, namely the fact that, globally, many Black people do not know how to swim. Owing to legacies of historical trauma relating to bodies of water, enforced migrations, colonialism, segregation, discrimination and stereotyping – and also surely a deep-seated respect for nature that recognises the vast and uncompromising power of the sea, swimming as leisure is not a pastime considered by many Black people as it is one that has been made complicated for us. The Black Swimming Association’s website states that: “95% of black adults and 80% of black children do not swim in England. 1 in 4 children who complete their primary education are unable to swim. According to the WHO, the risk of drowning is higher amongst minority ethnic communities.” I learned to swim as a child, but my mother did not, so even though she lives by the sea, every time I visit we do this sort of ritual where I help her to float in water. And every time she floats, she still laughs and says she can’t swim. I want to invite Black people to talk about swimming and their relationship with water, and these conversations, along with archival research, will become the grounding, the backbone, for written and audiovisual work, exploring the tension, intimacy, trust, floating, holding, fear, panic, vulnerability, growth, strength, compassion and healing felt when submerged in water.