Published:

What does it take to provide unconditional support to artists? How can galleries encourage the production of contemporary art?

Our current archive exhibition, Galleries in the Groove, ponders these questions by looking into the work of three visionary galleries between the 1960s-80s. Just Above Midtown (JAM) in New York, Robert Fraser Gallery in London and Antwerp’s Wide White Space each took great risks in order to offer opportunities to unsupported artists and open up their networks.

Here our current Asymmetry Curatorial Fellow, Zoe Diao, delves into the history of JAM and its unrealised ‘Afro-pop’ projects, offering a unique glimpse into a venue famous for representing artists of colour in district filled with mainstream dealers.

Installation view of Galleries in the Groove: Three Visionary Dealers, 1960s-80s at Whitechapel Gallery, 21 December 2021 – 21 August 2022. Photo: Damian Griffiths.

Installation view of Galleries in the Groove: Three Visionary Dealers, 1960s-80s at Whitechapel Gallery, 21 December 2021 – 21 August 2022. Photo: Damian Griffiths.As a young single mother from Ohio, Linda Goode Bryant moved to New York City in 1972 for Master’s programme in City College. After an internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and six months as a Rockefeller Fellow, she started working in the Studio Museum of Harlem. The moment of decision came when artist David Hammons told Bryant, “I don’t show in white galleries”.[i] Later in 1974, she borrowed $1000 and opened Just Above Midtown (JAM),[ii] a space exclusively dedicated to black artists and culture until its closure in 1986.

Like many avant-garde art dealers of her time, Bryant showed interest in unconventional art forms that were not, at the time, deemed acceptable for museums or the wider art market. At the same time, she realised the potential for an art gallery beyond commercial gains. To her a gallery could be a place of inclusivity, debate, innovation, education, artistic support, and beyond all, a place for creatives to share their own voices. So many artists’ stories we’ve heard since follow a similar patter: the artist’s work is first appreciated by a dealer, followed by successful, sold-out exhibitions and the recognition of larger audiences and institutional acquisition. However this classical mode of ‘making an artist’ does not necessarily apply to JAM. While the gallery promoted many artists who later became widely recognised and commercially successful, their careers were also born out of chaotic arguments, hard decisions and an experimental, risk-taking spirit.

On the other hand, however, JAM acted as more than a commercial art gallery and produced exhibitions, programmes and publications on an institutional scale. The location of the events also expanded from the gallery space into the cityscape. According to Lorraine O’Grady, “JAM was a place as much as a world, a place where people ate together, discussed and argued, drank and smoked together, collaborated on work, slept together, pushed each other to go further, and partied ’til the cows came home.”[iii] For Bryant, interaction in the gallery was “one big stew”, where JAM became a work of art in itself.[iv]

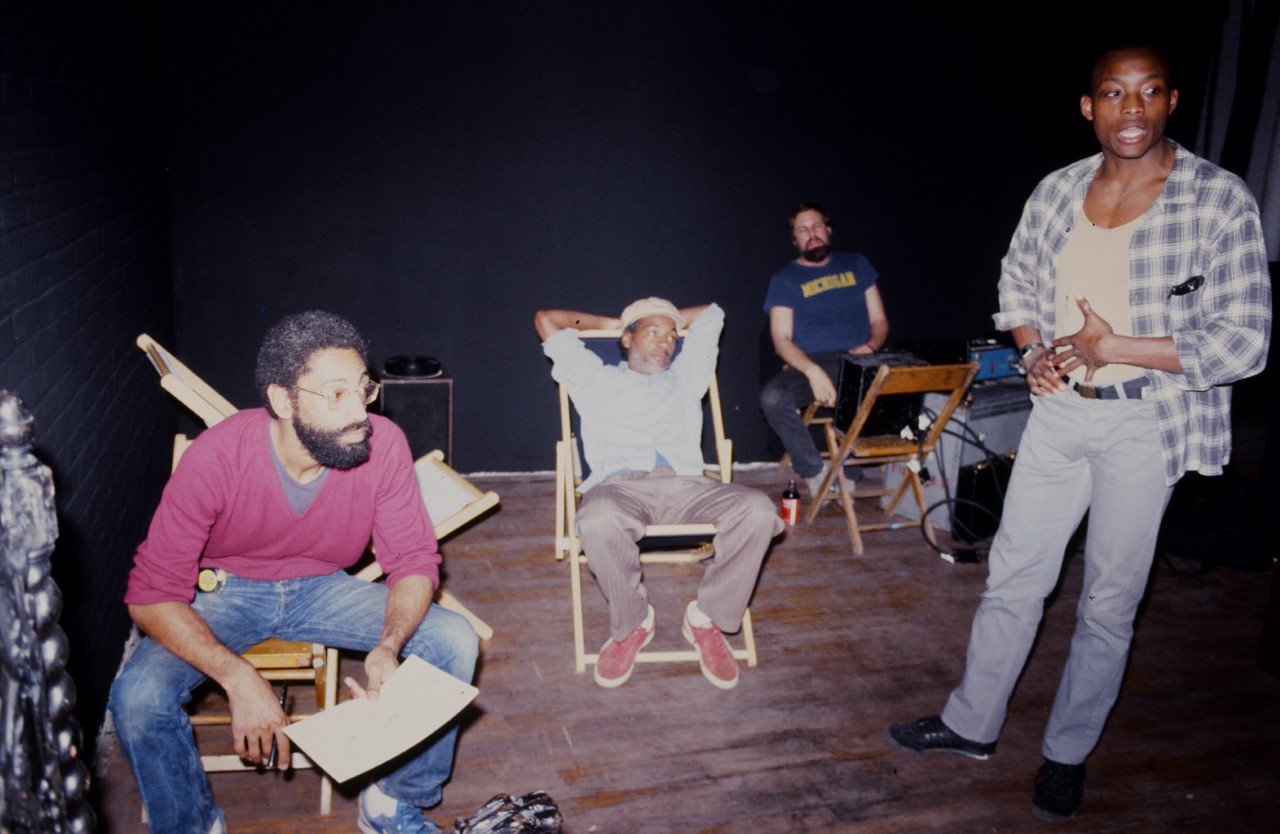

In 1982, JAM jumpstarted plans for a multidisciplinary exhibition titled, Afro-American Popular Culture: from the Saturday Night Stomp to the Sunday Morning Service. The project was to include installations by artists such as David Hammons, Senga Nengudi; performances by Adrian Piper, Lorraine O’Grady, Bill T. Jones, and Kaylynn Sullivan; oral history interviews with some of the participating black artists and dancers; a three-day music event in venues across New York City; a survey of black popular dance since the 1920s; a publication with essays and artworks, and numerous events on black humour, games, popular literature, graphic arts, beauty, cuisine, social clubs, entertainment and fashion.

Unfortunately this magnificent project, which some might say could have altered the entire art world, was never realised. We can only imagine the dazzling panorama through remaining documentations and files from the gallery’s archive. The oral histories project, for example, was conducted around 1982, featuring the recordings of interviews with Shirley Campbell, Senga Nengudi, Kaylynn Sullivan, dancer Margot Webb, and Bryant’s father and children. There are also recordings from meetings and conversations in the gallery as Bryant and her colleagues discussed how to promote the project. The catalogue drafts further feature essays on black humour, cooking, fashion, social clubs and organisations, by authors including John L. Gwaltney, David Langston Smyrl and Terry M. Williams.

Alongside the legacies of the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Art Movement and art collectives such as AfriCOBRA, JAM aimed to promote the visibility and recognition of black culture – a vision still sought after today. ’Afro-pop’ might have been one of the most important references to understand JAM, as we’re already familiar with the famous exhibitions and stories and its cultural and contextual importance. This unrealised series also offers insight into the ideas and ambitions at the core of JAM, something we are still working towards unearthing.

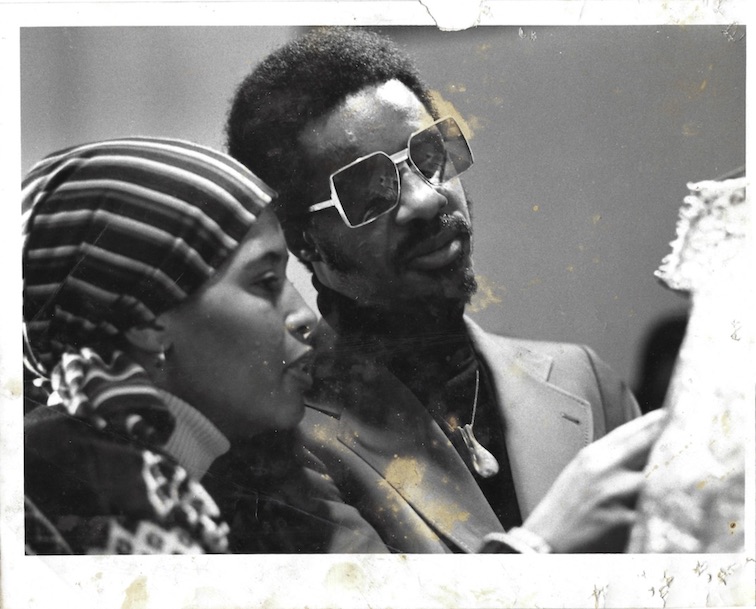

Linda Goode Bryant, 1973. Photo: Dwight Carter. Courtesy Linda Goode Bryant.

Linda Goode Bryant, 1973. Photo: Dwight Carter. Courtesy Linda Goode Bryant.

Notes

[i] See “Linda Goode Bryant by Rujeko Hockley”, BOMB (online), Apr 11, 2019. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/linda-goode-bryant/

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Quoted from Alex Greenberger “How New York’s Legendary Just Above Midtown Gallery Spurred Generations of Black Artists to Success”, ARTnews (online), April 6, 2021. https://www.artnews.com/feature/just-above-midtown-linda-goode-bryant-why-is-it-important-1234588859/

[iv] See Linda Goode Bryant and Senga Nengudi “The Gallery Where Stevie Wonder Was a Regular”, New York Times (online) July 2, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/02/t-magazine/linda-goode-bryant-senga-nengudi.html